East Side Story: How East London is losing its edge.

- Chloé Salmon

- Oct 4, 2022

- 5 min read

All black and white archival photographs were found online, credits are captioned. The rest were taken on my Fujifilm x100f, between March and April 2019.

I’ve always had a fraught relationship with Brick Lane. Full to the brim with tourists, stalls of all kinds spilling onto the street - Brick Lane on a weekend is consistently, spectacularly saturated . The show runs full-gas for the exclusive leisure and entertainment of the hip, the young, the visiting and whoever is equipped with disposable income, willing to give it up on specialty coffee worth an hour’s wage, cocktails served in mason jars and curiously overpriced vintage denim jackets. Yet amongst all the noise and commotion, it can feel somehow empty and vacuous, and most importantly, strangely incoherent.

Brick Lane and its surrounding area has progressively become a parody of itself. The East End was once a refuge for persecuted French Huguenots, Irish immigrants, Jewish refugees and Bengalis fleeing poverty and exercising their Commonwealth citizenship rights - and throughout the ages, a safe haven for pockets of avant-garde artists too broke to afford rent inside London’s fashionable bits. Following indiscriminate destruction and reconstruction, whatever is left of this past has been turned into a shopping mall for the new rich. Businesses are now capitalising on this historical palimpsest, selling chunks off to luxury high-rise property developers, ultimately targeting foreign investors with a knack for buying-to-let, with no care in world for the human cost of this ‘regeneration’.

I wanted to create this little series, as I have recently started developing a taste for photographic archives, and how these would enable a richer visual understanding of London’s evolution — in hopes of better grasping what’s being lost in the sweep of modernity.

Left to right, top to bottom: 1. Talking business at a flea market on Sclater Street, 2019. 2. Brick Lane in the 1980s by Sarah Ainslie. 3. At the intersection of Brick Lane and Sclater Street, 2019. 4. Same spot, 1978.

Left: Sclater Street Sunday Market, 2019. Right: Unlabelled, archives from Stefan Dickers.

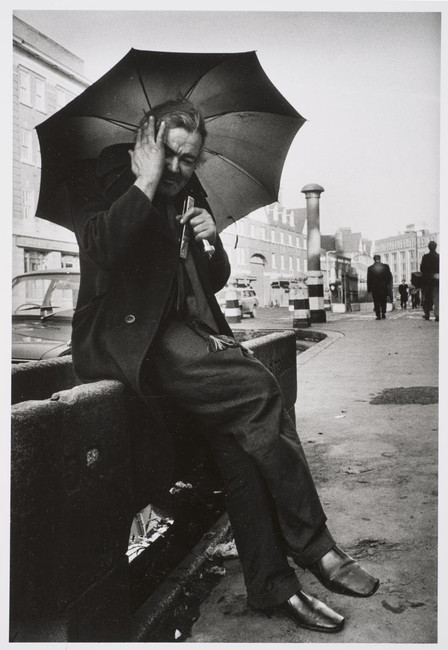

Left: Bethnal Green Road, 2019. Right: Man playing mouthorgan in front of Christ Church, Commercial Road, 1978, by Marketa Luskacova.

Left: A drunk orator on Brick Lane, 2019. Right: 9 year-old Charlie Long lived in a worker’s eating house run by his parents, Horace Warner, 1901.

The East End has always carried some kind of a bad rap, consistently marginalised as a breeding ground for the worse that humanity has to offer; destitution, decay, crime, drugs, prostitution, overcrowding— vice in all its forms. In the aftermath of Jack the Ripper’s ravages in the year 1888, it is safe to say the fate of Victorian East End was sealed — a grim reputation maintained well into the 20th century.

Reporting from 2019.

Gentrification essentially means that streets are sanitised and buildings in better shape. Yet most East London street have been destroyed and rebuilt or even simply renamed, as if the loaded history of these pavements could be washed away by a simple rewording. Whilst we don’t see starving children polishing shoes on the street anymore, it would be mistaken to conclude that gentrification has entailed the eradication of endemic poverty for good. Debt, forced relocation, precarious employment — modern signs of economic depravation are often out of sight.

Indeed, economic hardship is far from eradicated — London is ever more socially segregated. The borough of Tower Hamlets, home to all places captured above and below — was set to host the 2012 Olympic Games. The event had brought in a shiny £9.9 billion profit. Yet simultaneously, 52% of Tower Hamlets’ children are living below the poverty line. Who profits from gentrification? Answer: not the locals.

At the core of gentrification lies a logic of social cleansing (never publicly labelled as such though, that would be too distasteful): poverty is not tackled at the roots, it is moved further and further out of sight.

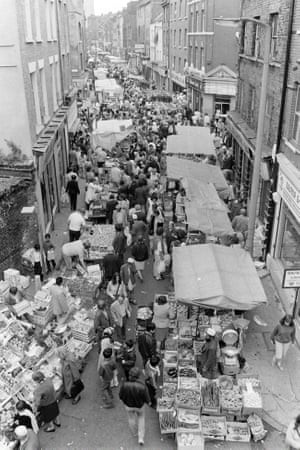

Markets are disappearing.

The East End was home to a furious amount of markets: most ramshackle and unofficial by nature. They consisted of a random display of possessions, and would have looked much like our markets today, after close of business. Markets were the source of livelihood for many, and the cornerstone of the social and communal lives of most. Today the remaining few have been recuperated as tourist traps, where people walk past, snap pictures, and rarely stop. (Brick Lane, Sclater Street, Chatsworth Road, Petticoat Lane, Roman road, Well Street, Whitechapel Market, Columbia Road Flower Market.)

Left: As Bengali immigration peaked in the mid-20th century, many found employment in the clothing and leather industries. A few remnants of the trade on Brick Lane, 2019. Right: Brick Lane Sunday market, 1985, Raju Vaidyanathan.

Left: Close of business on Sclater Street Yard — rumour has it the market will be closed down due to property development, 2019. Right: Back of Cheshire Street (Grimsby Street) market, 1986, Raju Vaidyanathan.

Selling Melons on Brick Lane. East London, 1985. Phil Maxwell

Left: Cleaning up after Sunday Market on Brick Lane, 2019. Right: Selling bananas on Brick Lane. East London, 1983. Phil Maxwell

Left: Bangla Town Cash and Carry, Hanbury Street, 2019. Right: Star Wholesale Cash and Carry, Commercial Street. East London 1988. Phil Maxwell.

Left: A couple decades ago, this would have been his neighbourhood, now he has to share with tourists. Right: spotted with goods from Columbia Road Market.

In comes capital, out go the poor.

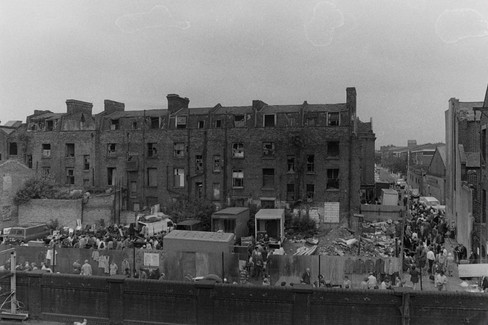

By late twentieth century, inner London suffered the trauma of de-industrialisation, i.e. the downward spiralling of the manufacturing and physical trades. The downfall of the Docks, closed to shipping in 1969, was accompanied by rising unemployment, Dickensian poverty, drug-related and gang-based crime. Many who could afford fleeing a now dilapidated East End, did. Inner/East London was left to the ‘problem population’.

Fast forward to the 80s. Margaret Thatcher’s London was synonym with the unleashing of unregulated finance, and happy days for our neocons. Her most pervasive legacy is perhaps the now common dictum that ‘business knows best’, a logic that ultimately permeated the management of property and housing. In an attempt to free London’s development business, Michael Heseltine (then Tory Secretary of State for the Environment), abolished the South East Economic Planning Council in 1979, on the grounds that social legislation stifled the economic potential of the area. It was replaced with the London Docklands Development Corporation (LDDC) two years later. In other words, regeneration now completely bypassed the government. Accent was put on luxury office development and attempts were made to attract international businesses through tax exemptions. Priority was not public housing, nor was it job creation, let alone jobs fit for traditional East End labour culture.

London’s boundary between affluent west and deprived east has been moving steadily eastward over the last 40 years. (Deyan Sudjic, The Language of Cities)

Modernity has brought a semblance of peace and prosperity to East London. But make no mistake, the inflow of capital translates into manic luxury property development (with less and less buyers), driving rent prices up to unaffordable levels, we know how the story ends.

Gentrification is a story we have been told, a story those in control enjoy telling themselves. But if we probe just a little we come to face with the real human price behind you being able to enjoy an oat milk chai latte at the same spot where an old guy set up shop sixty years ago serving pies and breakfast tea to his neighbourhood. If you prove a little deeper though, you might just find indifference. Most people simply aren’t that bothered…

Comments